Owing in large part to its relatively low cost and fat content, poultry has become America’s favorite meat. But problems with shopping, preparing, and cooking chicken at home abound—mostly because there are so many conflicting theories about how to handle it and cook it. Here’s what you need to know.

Labeling

Many claims cited on poultry packaging have no government regulation, while those that do are often poorly enforced. Here’s how to evaluate which claims are meaningful—and which are full of loopholes or empty hype.

Air-Chilled: “Air-chilled” means that chickens (or turkeys) were not water-chilled en masse in a chlorinated bath and the meat did not absorb any water during processing. (Water-chilled birds can retain up to 14 percent water—which must be printed on the label—diluting flavor and inflating cost.) Instead, individual chickens hang from a conveyor belt and circulate around a cold room.

USDA Organic: The seal “USDA Organic” is considered the gold standard for organic labeling. This label ensures that poultry eat organic feed that doesn’t contain animal byproducts, are raised without antibiotics, and have access to the outdoors (how much access, however, isn’t regulated).

Raised Without Antibiotics: “Raised without antibiotics” and other claims regarding antibiotic use are important; too bad they’re not strictly enforced. (The only rigorous enforcement is when the claim is subject to the USDA Organic seal.) Loopholes seem rife, like injecting the eggs—not the chickens—with antibiotics or feeding them feather meal laced with residual antibiotics from treated birds.

Natural and All Natural: Beware the ubiquitous “natural” and “all natural” food labels. In actuality, the USDA has defined the term just for fresh meat, stipulating only that no synthetic substances have been added to the cut. Producers may thus raise their chickens under the most unnatural circumstances on the most unnatural diets, inject birds with broth during processing, and still put the claim on their packaging.

Hormone-Free: When used with poultry (and pork) “hormone-free” is an empty reassurance, since the USDA does not allow the use of hormones or steroids in the production of either poultry or pork.

Vegetarian-Fed and Vegetarian Diet: “Vegetarian-fed” and “vegetarian diet” sound healthy, but are they? Since such terms aren’t regulated by the government, you’re relying on the producer’s notion of the claim, which may mean feeding chickens cheap “vegetarian” bakery leftovers. The winners of our whole chicken tasting assured us that their definitions mean a diet consisting of corn and soy.

Shopping for Chicken

Compared to beef and pork, which possess myriad cuts, often with alternate names, chicken can be less confusing to shop for at the market. That said, there are particular considerations you should be aware of when shopping for chicken.

Whole: Broilers, Fryers, and Roasters: Whole chickens come in various sizes. Broilers and fryers are younger chickens that weigh 2½ to 4½ pounds. A roaster (or oven-stuffer roaster) is an older chicken and usually weighs between 5 and 7 pounds.

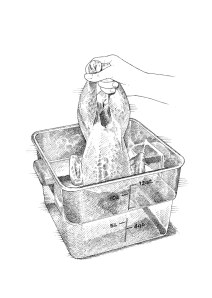

Our tasting and research proved processing is the major player in texture and flavor. We found that specimens that are “water-chilled” (see above) or “enhanced” (injected with broth and flavoring) are unnaturally spongy and are best avoided. Labeling law says water gain must be shown on the product label, so these should be easily identifiable. When buying a whole bird, look for those that are labeled “air-chilled” (in the test kitchen, we like Mary’s Free Range Air Chilled Chicken or Bell & Evans Air Chilled Premium Fresh Chicken). Without the excess water weight, we found these chickens to be less spongy in texture (but still plenty juicy) and to taste more chicken-y.

Bone-In Parts: You can buy a whole cut-up chicken or chicken parts at your supermarket, but sometimes it’s hard to tell by looking at the package if it’s been properly butchered. If you have a few minutes of extra time, consider buying a whole chicken and butchering it yourself (see how it’s done in our video tips).

Boneless, Skinless Breasts and Cutlets: If you’re buying boneless, skinless breasts, you should be aware that breasts of different sizes are often packaged together, which is a problem since they won’t cook through at the same rate. Try to pick a package with breasts of similar size, and pound them to an even thickness. We prefer Bell & Evans Air Chilled Boneless, Skinless Chicken Breasts.

You can buy cutlets ready to go at the grocery store, but we don’t recommend it. These cutlets are usually ragged and of various sizes; it’s better to cut your own cutlets from breasts.

Ground: Ground chicken is typically sold one of two ways: prepackaged or ground to order. The prepackaged variety is made from either dark or white meat. Higher-end markets and specialty markets grind their chicken to order, and therefore the choice of meat is yours. When it comes to flavor, however, our tasters were unanimous—dark meat is far superior. In most of our testing, we found ground white meat chicken to be exceedingly dry and almost void of flavor. The dark meat was more flavorful and juicy due to its higher fat content.

➜ This content is excerpted from the Poultry chapter from The Cook’s Illustrated Meat Book. See more inside the book.